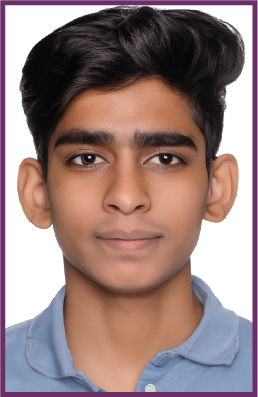

From Earning to Learning: Raju’s Journey

16-year-old Raju Kumar should have been poring over his schoolbooks. Instead, he was nearly a thousand miles from his home in rural Bihar, cutting diamonds in a dismal, unventilated factory in Surat, Gujarat state.

He hadn’t wanted to leave school - things had been looking up. Despite a staggeringly high dropout rate among his peers, he’d made it to the 10th grade, and had passed his crucial board exam. But then, economic calamity struck his family. His parents, landless day laborers themselves, found themselves facing destitution.

So, with a few friends, Raju set off on the journey to the state of Gujarat in western India, where 95% of the world’s diamonds are cut. Underage workers are among those doing the cutting, as some factory owners, enticed by easily exploitable, cheap labor, routinely flout child labor laws. Though the stones that Raju ground and polished day in and out for a meager wage might have been priceless, their value paled against that of his health, as well as his fast-slipping opportunity to live a better life.

Aside from being illegal, Raju’s work was hazardous: unskilled workers were left to use dangerous, powered cutting tools and faced respiratory exposure to "black diamond dust" thrown off by the process. It took only three months at the factory for Raju’s job to begin taking its toll on his young body. The repetitive labor, the cramped and unsanitary living conditions, and the constant inhalation of the black dust kept him chronically ill. He alerted his parents to his condition, but if his monthly salary of $107 USD suddenly halted, it would spell disaster for the family.

Raju’s story is all too common among children from Bihar state’s West Champaran district, located among the forests and hills near India's border with Nepal. Most of the people here belong to the indigenous Tharu and Oraon tribes, communities that face both poverty and discrimination. Due to a variety of factors, public amenities for children are non-functional: schools are poorly staffed and lack textbooks, safe drinking water, and separate toilets for girls. The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) centers – which are supposed to provide early-childhood health and nutrition services for infants and children up to age 6 and new mothers – are similarly hobbled by poor infrastructure and low staff accountability. Discouraged by the lack of resources and learning opportunities, children often lose interest in studies and drop out of school in favor of work. Pursuit of more lucrative earnings frequently leads children – mostly boys – to migrate to other states as early as age 13. Across India, the problem is endemic. According to India's 2011 census, there are 33 million children between the ages of 5 and 18 are engaged in labor. A detailed policy brief by our partner Child Rights and You in India notes that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic threatens to push even more into the work force.

CRY America’s project partner DEEP (Development Education and Environmental Programme) has been working on child protection and education issues in 24 villages in West Champaran. The causes of child labor are complex and cross-cutting; DEEP recognized that such a multi-layered problem requires a multi-layered intervention.

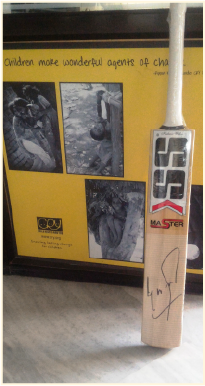

Children’s collective participation in their own development is a key theme in CRY America’s rights-based approach. To that end, the DEEP team helped to organize children’s collectives, which met regularly to discuss issues such as child labor and to identify and report child labor cases. Concurrently, DEEP coordinated anti-child labor workshops with village-level government officials, landowners, and small businesses. The participants designed and implemented use of a “Child Labor Free” sign, to be posted at establishments committed to the cause. DEEP also targeted household resource scarcity as a major root cause of child labor, by linking families in need to various social entitlement programs that provide guaranteed, paid work and regular food allotments.

Freshly empowered with awareness of their rights, the children's collectives were instrumental in identifying 363 boys and girls who were working locally as stone-crushers, field hands, and in shops. Through a series of persuasive discussions with parents, officials and employers, the DEEP team and the collectives were able to remove all of the children from the workforce and place them back into school.

Help for Raju was not far behind. DEEP launched a campaign directed at migrant child laborers, using rallies, street dramas acted out by children’s collective members, and meetings to raise awareness among parents of the ills of the practice. Raju’s parents came to understand that the lasting damage to their son’s well-being far outweighed his earnings.

Following a series of counseling sessions between Raju, his parents, and DEEP staff, Raju left his job and returned home. DEEP assisted him in re-enrolling in high school and provided him with free computer training at its Digital Literacy Center. He has since graduated and is well on his way to achieving his goal of becoming a government officer. In the meantime, he has become a valued volunteer trainer at the Digital Literacy Center, helping teach basic computer skills to other at-risk children.

"Child labor actually perpetuates poverty and unemployment,” says CRY America President Shefali Sunderlal. “Besides getting negligible wages, children’s rights are violated and their dreams shattered. Children who survive the harsh working conditions grow up to become unskilled, uneducated, unhealthy adults. We can break this harmful cycle of unemployed parents and working children by ensuring that all children go to - and stay in - school.”

CRY America’s experience confirms that parents in villages like Raju’s across India do value education and will do their best to ensure their children go to school. Through our project partners, CRY America has been working to eliminate obstacles to education, like lack of livelihood opportunities for parents and poorly resourced schools. The change is brought about through focused work with all of the stakeholders: teachers and schools, the children, their parents, the local community and local government agencies.

While barriers like child labor, girl child discrimination, migration, and displacement are being addressed, programs like evening classes and bridge education sessions prepare children for eventual mainstreaming into public school.

Often, this is an incremental process that takes time. But once a community is empowered with the awareness of their rights and the mechanisms by which to secure them, the change becomes self-sustaining. And we’ve seen great success from DEEP’s effort: thus far, they have ensured that 6,420 children go to school, 358 children have been removed from labor, 14 child marriages were stopped, and 480 children are part of the children’s collectives. Today, eight villages and slums are child-labor free.

Breaking Poverty’s Submission Hold: How Sanjana Wrestled Toward Opportunity

In the 2016 blockbuster Hindi film “Dangal”, Amir Khan plays a former champion wrestler who trains his daughters to eventually compete – and triumph – in the Commonwealth games. Based on the true story of Geeta and Babita Phogat and their father Mahavir Singh, it’s a powerful character study of two girls who shattered traditional gender roles in conservative rural India to become world-renowned athletes.

As an award-winning wrestler (and curler - more on that later!) herself, 15-year-old Sanjana's story resembles that of the Phogat sisters. However, it was a long road to that success. Her own personal background mirrored a more familiar Bollywood trope – that of family disapproval of intercommunal parentage.

Sanjana was born in rural Andhra Pradesh (south-central India) to a low-caste Hindu father and a Muslim mother. Her troubles began with her relatives’ refusal to accept her parents’ union. To make matters worse, her father died in an accident when she was only six years old.

Newly widowed and lacking support from immediate family, her mother moved Sanjana to her grandmother’s residence in nearby Chittoor district. Sanjana completed her primary education at public school, and is now studying in 10th standard at a public secondary school. However, her schoolwork was complicated by her work schedule. To make ends meet, her mother and grandmother prepared tiffins (lunchboxes containing hot meals) to be delivered to workers.

“It is difficult for me to wake up at 4:00 AM to help my mother in tiffin preparation process,” said Sanjana. “Along with that, I have to complete my homework.”

So it was that Sanjana found herself in a precarious position. Unfortunately, it was a common one for children living throughout the region, whose families, when faced with such household survival decisions, are at high risk of compelling them to drop out of school in order to help provide. As of December 2020, CRY America’s monitoring and evaluation team reported that 188 children had dropped out of school, and 115 children were engaged in labor in and around Sanjana’s home village.

Deep-rooted societal problems require solutions that are backed by comprehensive understanding - and that’s exactly what CRY America project partner Pragathi brings to the table. Established in 1993, Pragathi’s social justice work began in founder K.V. Ramana’s own hometown. Mr. Ramana has cultivated a body of hyper-local expertise about the conditions and issues of his community, which has informed Pragathi’s work on issues of education and protection for children chiefly from scheduled caste (legally recognized minority), indigenous, and other “backward” (India's legal designation of traditionally deprived peoples) communities. These families also take part in seasonal migration, taking up itinerant jobs in mango groves, as cattle-gazers, and as agricultural laborers. Sanjana’s village is one of 55 in Pragathi’s operational area in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh.

Children are pushed out of school for a number of reasons, due as much to glaring infrastructural gaps as household economic needs. One-third of children from migrating families travel along with the family, disrupting regular schooling. If they are accessible at all, schools themselves are often in dilapidated condition and ill-equipped for learning owing to insufficient funding. Girls in particular are at high risk of dropping out to take care of young siblings or to get married – itself a serious and interrelated problem. The COVID-19 pandemic proved to be another impetus: Over 50 additional area children dropped out of school amid lockdowns and closures.

CRY America project partners plan their interventions critically and strategically, with a focus on remedying the root causes of child-rights violations. A major driver of both child labor and child marriage is a lack of livelihood opportunities for parents. By providing a bulwark against destitution for low-income households, India’s government social safety net programs can alleviate what conditions compel parents to send children to work. Employment guarantee programs (initiatives similar to Roosevelt’s depression-era Works Progress Administration in the US) also offer fair pay for public infrastructural or agricultural work to qualifying individuals

Pragathi shares information on these and other available entitlement programs with the community, and connects families in need with them where appropriate. All the while, the organization promotes among parents the vast potential of girl children, and the importance that education plays in realizing it.

Thanks to Pragathi's assistance in applying for a pair of government programs, Sanjana’s mother began receiving a monthly pension for widows, and the family secured permanent housing. She encouraged Sanjana to explore her own potential through her pursuit of athletics. Sanjana continued to develop confidence in her abilities through her involvement with Pragathi's children’s collective, and progressed quickly as a gifted wrestler. In 2019, she traveled to Delhi to compete in a tournament, and subsequently captured a gold medal in the state level grappling competition. In 2021, she returned to Delhi with the support of her village government and brought home a bronze medal.

Sanjana’s career took a dramatic turn this past January, when she won a gold medal in the first National Ice Curling Competition in Jammu & Kashmir as part of the Andhra Pradesh women's team. Remarkably, she accomplished this feat with minimal practice, proving herself as a natural as well as a pioneer in the sport!

Sanjana tells us that her dream is to become a police officer. Her discipline and determination are sure to carry her across that goal line in record time.

Pragathi continues to make impressive strides, despite challenges over the past year presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, 28 children were rescued from child labor and over half of that total were re-enrolled in school, thanks in part to Pragathi-organized teacher visits to the children’s homes. Some other accomplishments throughout Chittoor district over the past year include:

- Strengthening 12 Anganwadi Centers (government facilities that provide early childhood health care and nutritional support), which are now delivering preschool education for children ages 3-6.

- Enrolling 182 children in the preschool program.

- Recognizing that ongoing triage is essential in tailoring child labor-prevention programming, Pragathi identified 197 children who are at-risk of falling into child labor, and 234 children who were already combining work with school. Children were observed working in shops and as street vendors, harvesting flowers, performing agricultural work, and rearing cattle.

- Organizing confidence-boosting “Life Skills” instruction sessions to supplement schooling for 2,824 children from 73 children’s groups. The sessions covered self-empowerment, self-confidence, proactive thinking, problem-solving, verbal communication, body language, listening skills, and emotional intelligence.

- Presenting special, women-focused sessions on health, safety and hygiene to 35 adolescent girls' collectives.

As CRY America volunteers, staff and leaders, we are continually inspired by the dedication of our partners in the field to do our part in raising funds for the cause and awareness of the issues.

“Every child is unique, every child is precious and should have a dignified, happy and cherished childhood, free from the clutches of child labor, fear, poverty, and diseases,” says Rajesh Munshi, leader of CRY America’s Seattle Volunteer Action Center. “I feel that nothing is more important than ensuring that the fundamental rights of children are protected.”

“These children don’t get the same start in life as the privileged have,” says Soumya, volunteer with the San Diego Action Center. “When children’s rights are protected, children stand a much better chance of growing up in a society that allows them to thrive,”

“I’ve gotten to witness the journeys of the children that have grown and accomplished so much under the shadow of CRY,” says Naimishah, of our Atlanta student volunteer Action Center. “It keeps me striving to do whatever I can to aid.”

“Children's rights should be at the core of policies and our everyday choices should address the root causes that impede children's progress,” says CRY America CEO Shefali Sunderlal. “CRY America has one simple aim - to put children ahead.”