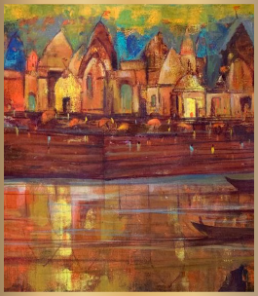

Rural Workers’ Development Society, Tamil Nadu

Striking at the Roots of Child Labor: Rural Workers’ Development Society, Tamil Nadu

CRY America acknowledges with gratitude the Guru Krupa Foundation, whose generous gift of $20,000 ensures that the noble work of RWDS may continue.

Sowmiya (17) and her classmates had grown to dread the daily 4-kilometer walk from their village of Ayyanarpuram to school. The unhappy morning trudge through farmers’ fields and over rough terrain in the rural, palm grove-flush Ramanathapuram district of Tamil Nadu left the 21 students regularly demoralized and often late for class. Once classes finished, they faced the fatigue of the return trip. According to Sowmiya, many had become resentful not only of having to attend school under such conditions, but even the idea of education itself.

The rainy seasons brought both insult and injury for the weary kids. “Walking through the fields during rainy days, I have at times fallen and been hurt,” said Sowmiya. “All my notebooks become spoiled, and I will be entirely drenched when I enter the classroom.”

Children from over half of the 52 district villages where CRY America project partner Rural Workers Development Society (RWDS) works contended with challenges identical to those of Sowmiya and her friends. Too often, it’s a lack of affordable transportation, or an absence of a road between a residence and the closest school that contributes to a family’s decision to withdraw a child - often, due to safety concerns, a daughter - from class. Moreover, the preponderance of unaffordable private schools creates another layer of inaccessibility. RWDS reported that at the outset of 2021, out of a total 2,800 area children between ages 11 and 18, 800 dropout boys and girls were engaged in illegal child labor. The overall dropout rate for children 6-18 years of age topped a staggering 46% - over half of which were girls.

The RWDS team set about taking corrective action, armed with local expertise and rafts of baseline data (made possible in part through CRY America’s support). The team established two major goals toward closing the education gap: Reduce the dropout rate among children aged 6-18 to 20% and raise the percentage of children who remained in school once enrolled from 70% to 80%. Concurrently, RWDS undertook steps to ensure physical access to schools, and to improve infrastructure and quality within schools and Integrated Child Development Service centers (Government of India-administered early childhood health facilities).

Through direct home visits to families of at-risk children, distribution of posters and other outreach materials on the importance of education and the harms of child labor, the RWDS team identified 3,473 children for monitoring and follow-up to ensure that they have been enrolled in school and are attending regularly.

After surveying the scenario of children of the palm field-workers and conducting outreach to households, RWDS successfully re-enrolled 919 children in nearby schools. To pre-empt dropout in 11 villages where children were at most risk of doing so, RWDS organized supplemental courses led by community volunteers. The courses ensured that 380 students in first to eighth standard remained engaged in reading, writing and other subjects.

RWDS staff conducted public discussions with village Sangams (traditional community group), engaging with 241 community members, 87 parents of child laborers, and the child laborers themselves. In these sessions, the team emphasized the importance of continuing children’s education and built popular awareness on the serious and permanent harm visited upon child laborers. In the process, RWDS removed 12 children from labor situations, 5 of whom were re-enrolled in high- and high-secondary school.

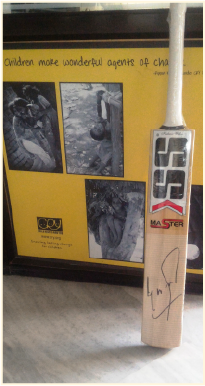

Sowmiya’s predicament only recently came to a fruitful conclusion - thanks to the work of the entire village community, as well as the local children’s collective and the guidance offered by RWDS. Over 200 kids from her community now benefit from the safe and accessible route to school that the new road provides. CRY America Director of Fundraising, Patrick Bocco, recently visited RWDS in October and saw firsthand this new road and major achievement!

“We tried all the ways to bring the bridge and the road to make our way easier. As a part of our children’s collective, we sent handmade postcards to the Chief Minister. With the help of the palm workers’ sangam, we gave a petition to the district collector. Finally, the day came! After all these years, we got our road in 2022! Now I have completed my school, but I am so happy for my tiny brothers and sisters knowing that they are not going to struggle while going to school!” This is one of many success stories thankfully made possible due to the ongoing support of the Guru Krupa Foundation!

An Ambassador Grows in Madanapalle…

Revathi’s grandparents feared the worst for her.

For three years since she and her older sister moved to a slum in the town of Madanapalle in Andhra Pradesh to live with her grandparents, her engagement with the outside world was minimal. Ironically enough, her parents had sent the girls to town in pursuit of educational opportunities, since their native village of Divitivaripalle had only one primary school. Concerned for the girls’ safety, the well-meaning grandparents imposed strict ground rules on their movements and associations, which ultimately interfered with her regular schooling. Though this way of life indeed kept her out of trouble, it left her thoroughly disappointed, lonely and demoralized - where was this opportunity she’d been promised? What was in her future?

In 2013, Revathi answered the door to her grandparents’ home to a staff member of People’s Organization for Rural Development (PORD), a CRY America-supported organization that was in the midst of a door-to-door child rights-awareness campaign. The PORD staffer invited Revathi to join the new children’s collective that had been formed in her neighborhood. Seeing that the collective had been organized by PORD, Revathi’s grandparents agreed to allow her to join. For Revathi, this was just the beginning of a whole new chapter she’d never dreamed of.

PORD was founded in 1992 by J. Lalithamma (and if you followed our 2022 “Heroes for Life” Gala series, you will know Ms. Lalithamma from her charismatic talks about her work). Ms. Lalithamma herself grew up in a village in Chittoor district, where PORD now works; as such, she was sadly familiar with the obstacles that girls still face.

Lalithamma was born to a Dalit family in one of Chittoor’s tiny hamlets. As lower-caste individuals, her family and neighbors in the village were accustomed to being marginalized by wider society as a perceived minority. Even within her community, conservative patriarchal norms dictated that girls were third-class citizens. By continuing a girl’s schooling past a certain point, parents ran the risk of rendering her “unmarriable” to local boys. And if that were to happen, a family would regard the daughter as nothing more than another mouth to feed - a liability at best, and a blot upon the family’s honor at worst.

When Lalithamma’s parents sought to pull her out of school in 5th grade, she knew even then that she had found her personal cause. Despite the resistance from family and community, she refused to go silently. Precocious and determined, Lalithamma went on a Gandhian hunger strike until her parents relented and allowed her to continue her education.

In her primary and upper-primary classes, Lalithamma thrived. However, her parents re-applied the pressure on her to drop out and marry before her secondary schooling (starting at grade 10 in India). Armed with education and confidence, Lalithamma again advocated for herself in persuading her parents to hold off on those designs until she finished her schooling entirely.

Lalithamma married eventually, but not before becoming a pre-primary schoolteacher. She never forgot the struggles that she overcame, and set about creating PORD as a means of helping little girls out of similar situations.

Meanwhile, Revathi was beginning to tread in Lalithamma’s footsteps as a social reformer through her involvement in the collective.

“I made sure I participated in every possible activity of the child collective,” Revathi told us. “I found my calling when I learned about child rights. It gave me a means to deal with the problem of child-rights abuse which was all around me in the slum. I now had a tool to act on it. The vulnerability and innocence of children moved me to spread awareness about child rights and mechanisms to protect them.”

Driven by boundless enthusiasm - and mentored by staff and Lalithamma herself - Revathi started participating in child rights capacity-building training sessions. She became a tenacious motivator and community whistleblower: engaging with out-of-school children through PORD’s annual enrollment campaigns, and alerting PORD staff to any child marriages that occurred in the slum. Soon after, she was made the Secretary of the children’s collective, and she became interested in visiting schools to educate other girls about the subject of menstrual hygiene (a taboo topic in the conservative villages).

Revathi’s hygiene and child-rights outreach work to over 5,000 girls netted her a Youth Changemaker Award from the Ashoka Foundation. Her newfound confidence fueled her pursuit of a college degree in technology. Today, Revathi works at Wipro (one of India’s largest IT companies) and continues her hygiene programs among girls.

Revathi’s story is just one of the “virtuous cycles” that we witness in the work of the projects that we support. Experience has shown us that true sustainability results when the torch is passed from the mentor to the new child-rights ambassador - who in turn inspires children and community alike.

From Earning to Learning: Raju’s Journey

16-year-old Raju Kumar should have been poring over his schoolbooks. Instead, he was nearly a thousand miles from his home in rural Bihar, cutting diamonds in a dismal, unventilated factory in Surat, Gujarat state.

He hadn’t wanted to leave school - things had been looking up. Despite a staggeringly high dropout rate among his peers, he’d made it to the 10th grade, and had passed his crucial board exam. But then, economic calamity struck his family. His parents, landless day laborers themselves, found themselves facing destitution.

So, with a few friends, Raju set off on the journey to the state of Gujarat in western India, where 95% of the world’s diamonds are cut. Underage workers are among those doing the cutting, as some factory owners, enticed by easily exploitable, cheap labor, routinely flout child labor laws. Though the stones that Raju ground and polished day in and out for a meager wage might have been priceless, their value paled against that of his health, as well as his fast-slipping opportunity to live a better life.

Aside from being illegal, Raju’s work was hazardous: unskilled workers were left to use dangerous, powered cutting tools and faced respiratory exposure to "black diamond dust" thrown off by the process. It took only three months at the factory for Raju’s job to begin taking its toll on his young body. The repetitive labor, the cramped and unsanitary living conditions, and the constant inhalation of the black dust kept him chronically ill. He alerted his parents to his condition, but if his monthly salary of $107 USD suddenly halted, it would spell disaster for the family.

Raju’s story is all too common among children from Bihar state’s West Champaran district, located among the forests and hills near India's border with Nepal. Most of the people here belong to the indigenous Tharu and Oraon tribes, communities that face both poverty and discrimination. Due to a variety of factors, public amenities for children are non-functional: schools are poorly staffed and lack textbooks, safe drinking water, and separate toilets for girls. The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) centers – which are supposed to provide early-childhood health and nutrition services for infants and children up to age 6 and new mothers – are similarly hobbled by poor infrastructure and low staff accountability. Discouraged by the lack of resources and learning opportunities, children often lose interest in studies and drop out of school in favor of work. Pursuit of more lucrative earnings frequently leads children – mostly boys – to migrate to other states as early as age 13. Across India, the problem is endemic. According to India's 2011 census, there are 33 million children between the ages of 5 and 18 are engaged in labor. A detailed policy brief by our partner Child Rights and You in India notes that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic threatens to push even more into the work force.

CRY America’s project partner DEEP (Development Education and Environmental Programme) has been working on child protection and education issues in 24 villages in West Champaran. The causes of child labor are complex and cross-cutting; DEEP recognized that such a multi-layered problem requires a multi-layered intervention.

Children’s collective participation in their own development is a key theme in CRY America’s rights-based approach. To that end, the DEEP team helped to organize children’s collectives, which met regularly to discuss issues such as child labor and to identify and report child labor cases. Concurrently, DEEP coordinated anti-child labor workshops with village-level government officials, landowners, and small businesses. The participants designed and implemented use of a “Child Labor Free” sign, to be posted at establishments committed to the cause. DEEP also targeted household resource scarcity as a major root cause of child labor, by linking families in need to various social entitlement programs that provide guaranteed, paid work and regular food allotments.

Freshly empowered with awareness of their rights, the children's collectives were instrumental in identifying 363 boys and girls who were working locally as stone-crushers, field hands, and in shops. Through a series of persuasive discussions with parents, officials and employers, the DEEP team and the collectives were able to remove all of the children from the workforce and place them back into school.

Help for Raju was not far behind. DEEP launched a campaign directed at migrant child laborers, using rallies, street dramas acted out by children’s collective members, and meetings to raise awareness among parents of the ills of the practice. Raju’s parents came to understand that the lasting damage to their son’s well-being far outweighed his earnings.

Following a series of counseling sessions between Raju, his parents, and DEEP staff, Raju left his job and returned home. DEEP assisted him in re-enrolling in high school and provided him with free computer training at its Digital Literacy Center. He has since graduated and is well on his way to achieving his goal of becoming a government officer. In the meantime, he has become a valued volunteer trainer at the Digital Literacy Center, helping teach basic computer skills to other at-risk children.

"Child labor actually perpetuates poverty and unemployment,” says CRY America President Shefali Sunderlal. “Besides getting negligible wages, children’s rights are violated and their dreams shattered. Children who survive the harsh working conditions grow up to become unskilled, uneducated, unhealthy adults. We can break this harmful cycle of unemployed parents and working children by ensuring that all children go to - and stay in - school.”

CRY America’s experience confirms that parents in villages like Raju’s across India do value education and will do their best to ensure their children go to school. Through our project partners, CRY America has been working to eliminate obstacles to education, like lack of livelihood opportunities for parents and poorly resourced schools. The change is brought about through focused work with all of the stakeholders: teachers and schools, the children, their parents, the local community and local government agencies.

While barriers like child labor, girl child discrimination, migration, and displacement are being addressed, programs like evening classes and bridge education sessions prepare children for eventual mainstreaming into public school.

Often, this is an incremental process that takes time. But once a community is empowered with the awareness of their rights and the mechanisms by which to secure them, the change becomes self-sustaining. And we’ve seen great success from DEEP’s effort: thus far, they have ensured that 6,420 children go to school, 358 children have been removed from labor, 14 child marriages were stopped, and 480 children are part of the children’s collectives. Today, eight villages and slums are child-labor free.

Breaking Poverty’s Submission Hold: How Sanjana Wrestled Toward Opportunity

In the 2016 blockbuster Hindi film “Dangal”, Amir Khan plays a former champion wrestler who trains his daughters to eventually compete – and triumph – in the Commonwealth games. Based on the true story of Geeta and Babita Phogat and their father Mahavir Singh, it’s a powerful character study of two girls who shattered traditional gender roles in conservative rural India to become world-renowned athletes.

As an award-winning wrestler (and curler - more on that later!) herself, 15-year-old Sanjana's story resembles that of the Phogat sisters. However, it was a long road to that success. Her own personal background mirrored a more familiar Bollywood trope – that of family disapproval of intercommunal parentage.

Sanjana was born in rural Andhra Pradesh (south-central India) to a low-caste Hindu father and a Muslim mother. Her troubles began with her relatives’ refusal to accept her parents’ union. To make matters worse, her father died in an accident when she was only six years old.

Newly widowed and lacking support from immediate family, her mother moved Sanjana to her grandmother’s residence in nearby Chittoor district. Sanjana completed her primary education at public school, and is now studying in 10th standard at a public secondary school. However, her schoolwork was complicated by her work schedule. To make ends meet, her mother and grandmother prepared tiffins (lunchboxes containing hot meals) to be delivered to workers.

“It is difficult for me to wake up at 4:00 AM to help my mother in tiffin preparation process,” said Sanjana. “Along with that, I have to complete my homework.”

So it was that Sanjana found herself in a precarious position. Unfortunately, it was a common one for children living throughout the region, whose families, when faced with such household survival decisions, are at high risk of compelling them to drop out of school in order to help provide. As of December 2020, CRY America’s monitoring and evaluation team reported that 188 children had dropped out of school, and 115 children were engaged in labor in and around Sanjana’s home village.

Deep-rooted societal problems require solutions that are backed by comprehensive understanding - and that’s exactly what CRY America project partner Pragathi brings to the table. Established in 1993, Pragathi’s social justice work began in founder K.V. Ramana’s own hometown. Mr. Ramana has cultivated a body of hyper-local expertise about the conditions and issues of his community, which has informed Pragathi’s work on issues of education and protection for children chiefly from scheduled caste (legally recognized minority), indigenous, and other “backward” (India's legal designation of traditionally deprived peoples) communities. These families also take part in seasonal migration, taking up itinerant jobs in mango groves, as cattle-gazers, and as agricultural laborers. Sanjana’s village is one of 55 in Pragathi’s operational area in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh.

Children are pushed out of school for a number of reasons, due as much to glaring infrastructural gaps as household economic needs. One-third of children from migrating families travel along with the family, disrupting regular schooling. If they are accessible at all, schools themselves are often in dilapidated condition and ill-equipped for learning owing to insufficient funding. Girls in particular are at high risk of dropping out to take care of young siblings or to get married – itself a serious and interrelated problem. The COVID-19 pandemic proved to be another impetus: Over 50 additional area children dropped out of school amid lockdowns and closures.

CRY America project partners plan their interventions critically and strategically, with a focus on remedying the root causes of child-rights violations. A major driver of both child labor and child marriage is a lack of livelihood opportunities for parents. By providing a bulwark against destitution for low-income households, India’s government social safety net programs can alleviate what conditions compel parents to send children to work. Employment guarantee programs (initiatives similar to Roosevelt’s depression-era Works Progress Administration in the US) also offer fair pay for public infrastructural or agricultural work to qualifying individuals

Pragathi shares information on these and other available entitlement programs with the community, and connects families in need with them where appropriate. All the while, the organization promotes among parents the vast potential of girl children, and the importance that education plays in realizing it.

Thanks to Pragathi's assistance in applying for a pair of government programs, Sanjana’s mother began receiving a monthly pension for widows, and the family secured permanent housing. She encouraged Sanjana to explore her own potential through her pursuit of athletics. Sanjana continued to develop confidence in her abilities through her involvement with Pragathi's children’s collective, and progressed quickly as a gifted wrestler. In 2019, she traveled to Delhi to compete in a tournament, and subsequently captured a gold medal in the state level grappling competition. In 2021, she returned to Delhi with the support of her village government and brought home a bronze medal.

Sanjana’s career took a dramatic turn this past January, when she won a gold medal in the first National Ice Curling Competition in Jammu & Kashmir as part of the Andhra Pradesh women's team. Remarkably, she accomplished this feat with minimal practice, proving herself as a natural as well as a pioneer in the sport!

Sanjana tells us that her dream is to become a police officer. Her discipline and determination are sure to carry her across that goal line in record time.

Pragathi continues to make impressive strides, despite challenges over the past year presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, 28 children were rescued from child labor and over half of that total were re-enrolled in school, thanks in part to Pragathi-organized teacher visits to the children’s homes. Some other accomplishments throughout Chittoor district over the past year include:

- Strengthening 12 Anganwadi Centers (government facilities that provide early childhood health care and nutritional support), which are now delivering preschool education for children ages 3-6.

- Enrolling 182 children in the preschool program.

- Recognizing that ongoing triage is essential in tailoring child labor-prevention programming, Pragathi identified 197 children who are at-risk of falling into child labor, and 234 children who were already combining work with school. Children were observed working in shops and as street vendors, harvesting flowers, performing agricultural work, and rearing cattle.

- Organizing confidence-boosting “Life Skills” instruction sessions to supplement schooling for 2,824 children from 73 children’s groups. The sessions covered self-empowerment, self-confidence, proactive thinking, problem-solving, verbal communication, body language, listening skills, and emotional intelligence.

- Presenting special, women-focused sessions on health, safety and hygiene to 35 adolescent girls' collectives.

As CRY America volunteers, staff and leaders, we are continually inspired by the dedication of our partners in the field to do our part in raising funds for the cause and awareness of the issues.

“Every child is unique, every child is precious and should have a dignified, happy and cherished childhood, free from the clutches of child labor, fear, poverty, and diseases,” says Rajesh Munshi, leader of CRY America’s Seattle Volunteer Action Center. “I feel that nothing is more important than ensuring that the fundamental rights of children are protected.”

“These children don’t get the same start in life as the privileged have,” says Soumya, volunteer with the San Diego Action Center. “When children’s rights are protected, children stand a much better chance of growing up in a society that allows them to thrive,”

“I’ve gotten to witness the journeys of the children that have grown and accomplished so much under the shadow of CRY,” says Naimishah, of our Atlanta student volunteer Action Center. “It keeps me striving to do whatever I can to aid.”

“Children's rights should be at the core of policies and our everyday choices should address the root causes that impede children's progress,” says CRY America CEO Shefali Sunderlal. “CRY America has one simple aim - to put children ahead.”