Revathi’s grandparents feared the worst for her.

For three years since she and her older sister moved to a slum in the town of Madanapalle in Andhra Pradesh to live with her grandparents, her engagement with the outside world was minimal. Ironically enough, her parents had sent the girls to town in pursuit of educational opportunities, since their native village of Divitivaripalle had only one primary school. Concerned for the girls’ safety, the well-meaning grandparents imposed strict ground rules on their movements and associations, which ultimately interfered with her regular schooling. Though this way of life indeed kept her out of trouble, it left her thoroughly disappointed, lonely and demoralized – where was this opportunity she’d been promised? What was in her future?

In 2013, Revathi answered the door to her grandparents’ home to a staff member of People’s Organization for Rural Development (PORD), a CRY America-supported organization that was in the midst of a door-to-door child rights-awareness campaign. The PORD staffer invited Revathi to join the new children’s collective that had been formed in her neighborhood. Seeing that the collective had been organized by PORD, Revathi’s grandparents agreed to allow her to join. For Revathi, this was just the beginning of a whole new chapter she’d never dreamed of.

PORD was founded in 1992 by J. Lalithamma (and if you followed our 2022 “Heroes for Life” Gala series, you will know Ms. Lalithamma from her charismatic talks about her work). Ms. Lalithamma herself grew up in a village in Chittoor district, where PORD now works; as such, she was sadly familiar with the obstacles that girls still face.

Lalithamma was born to a Dalit family in one of Chittoor’s tiny hamlets. As lower-caste individuals, her family and neighbors in the village were accustomed to being marginalized by wider society as a perceived minority. Even within her community, conservative patriarchal norms dictated that girls were third-class citizens. By continuing a girl’s schooling past a certain point, parents ran the risk of rendering her “unmarriable” to local boys. And if that were to happen, a family would regard the daughter as nothing more than another mouth to feed – a liability at best, and a blot upon the family’s honor at worst.

When Lalithamma’s parents sought to pull her out of school in 5th grade, she knew even then that she had found her personal cause. Despite the resistance from family and community, she refused to go silently. Precocious and determined, Lalithamma went on a Gandhian hunger strike until her parents relented and allowed her to continue her education.

In her primary and upper-primary classes, Lalithamma thrived. However, her parents re-applied the pressure on her to drop out and marry before her secondary schooling (starting at grade 10 in India). Armed with education and confidence, Lalithamma again advocated for herself in persuading her parents to hold off on those designs until she finished her schooling entirely.

Lalithamma married eventually, but not before becoming a pre-primary schoolteacher. She never forgot the struggles that she overcame, and set about creating PORD as a means of helping little girls out of similar situations.

Meanwhile, Revathi was beginning to tread in Lalithamma’s footsteps as a social reformer through her involvement in the collective.

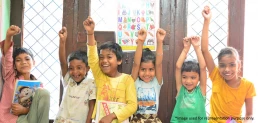

“I made sure I participated in every possible activity of the child collective,” Revathi told us. “I found my calling when I learned about child rights. It gave me a means to deal with the problem of child-rights abuse which was all around me in the slum. I now had a tool to act on it. The vulnerability and innocence of children moved me to spread awareness about child rights and mechanisms to protect them.”

Driven by boundless enthusiasm – and mentored by staff and Lalithamma herself – Revathi started participating in child rights capacity-building training sessions. She became a tenacious motivator and community whistleblower: engaging with out-of-school children through PORD’s annual enrollment campaigns, and alerting PORD staff to any child marriages that occurred in the slum. Soon after, she was made the Secretary of the children’s collective, and she became interested in visiting schools to educate other girls about the subject of menstrual hygiene (a taboo topic in the conservative villages).

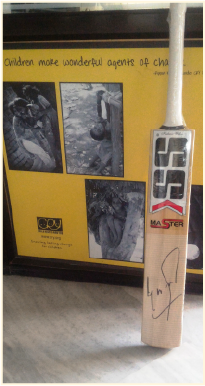

Revathi’s hygiene and child-rights outreach work to over 5,000 girls netted her a Youth Changemaker Award from the Ashoka Foundation. Her newfound confidence fueled her pursuit of a college degree in technology. Today, Revathi works at Wipro (one of India’s largest IT companies) and continues her hygiene programs among girls.

Revathi’s story is just one of the “virtuous cycles” that we witness in the work of the projects that we support. Experience has shown us that true sustainability results when the torch is passed from the mentor to the new child-rights ambassador – who in turn inspires children and community alike.

Recommended for you